Boris Pasternak

Boris Pasternak | |

|---|---|

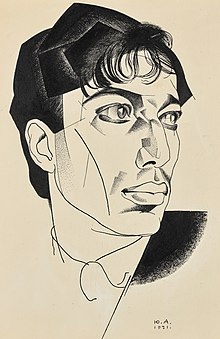

Pasternak in 1959 | |

| Born | Boris Leonidovich Pasternak 10 February [O.S. 29 January] 1890 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 30 May 1960 (aged 70) Peredelkino, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Occupation | Poet, writer |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire (1890–1917) Soviet Russia (1917–1922) Soviet Union (1922–1960) |

| Notable works | My Sister, Life, The Second Birth, Doctor Zhivago |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature (1958) |

| Parents | Leonid Pasternak and Rosa Kaufman |

| Relatives | Lydia Pasternak Slater (sister); Yevgeny Pasternak (son) |

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (/ˈpæstərnæk/;[1] Russian: Борис Леонидович Пастернак, IPA: [bɐˈrʲis lʲɪɐˈnʲidəvʲɪtɕ pəstɨrˈnak];[2] 10 February [O.S. 29 January] 1890 – 30 May 1960) was a Russian poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, My Sister, Life, was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an important collection in the Russian language. Pasternak's translations of stage plays by Goethe, Schiller, Calderón de la Barca and Shakespeare remain very popular with Russian audiences.

Pasternak was the author of Doctor Zhivago (1957), a novel that takes place between the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the Second World War. Doctor Zhivago was rejected for publication in the USSR, but the manuscript was smuggled to Italy and was first published there in 1957.[3]

Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1958, an event that enraged the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which forced him to decline the prize. In 1989, Pasternak's son Yevgeny finally accepted the award on his father's behalf. Doctor Zhivago has been part of the main Russian school curriculum since 2003.[4]

Early life[edit]

Pasternak was born in Moscow on 10 February (Gregorian), 1890 (29 January, Julian) into a wealthy, assimilated Jewish family.[5] His father was the post-Impressionist painter Leonid Pasternak, who taught as a professor at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. His mother was Rosa Kaufman, a concert pianist and the daughter of Odessa industrialist Isadore Kaufman and his wife. Pasternak had a younger brother, Alex, and two sisters, Lydia and Josephine. The family claimed descent on the paternal line from Isaac Abarbanel, the famous 15th-century Sephardic Jewish philosopher, Bible commentator, and treasurer of Portugal.[6]

Early education[edit]

From 1904 to 1907, Boris Pasternak was the cloister-mate of Peter Minchakievich (1890–1963) in Holy Dormition Pochayev Lavra (now in Ukraine). Minchakievich came from an Orthodox Ukrainian family and Pasternak came from a Jewish family. Some confusion has arisen as to Pasternak attending a military academy in his boyhood years. The uniforms of their monastery Cadet Corp were only similar to those of The Czar Alexander the Third Military Academy, as Pasternak and Minchakievich never attended any military academy. Most schools used a distinctive military-looking uniform particular to them as was the custom of the time in Eastern Europe and Russia. Boyhood friends, they parted in 1908, friendly but with different politics, never to see each other again. Pasternak went to the Moscow Conservatory to study music (later Germany to study philosophy), and Minchakievich went to Lvov University to study history and philosophy. The good dimension of the character Strelnikov in Dr. Zhivago is based upon Peter Minchakievich. Several of Pasternak's characters are composites. After World War One and the Revolution, fighting for the Provisional or Republican government under Kerensky, and then escaping a Communist jail and execution, Minchakievich trekked across Siberia in 1917 and became an American citizen. Pasternak stayed in Russia.

In a 1959 letter to Jacqueline de Proyart, Pasternak recalled:

I was baptized as a child by my nanny, but because of the restrictions imposed on Jews, particularly in the case of a family which was exempt from them and enjoyed a certain reputation in view of my father's standing as an artist, there was something a little complicated about this, and it was always felt to be half-secret and intimate, a source of rare and exceptional inspiration rather than being calmly taken for granted. I believe that this is at the root of my distinctiveness. Most intensely of all my mind was occupied by Christianity in the years 1910–12, when the main foundations of this distinctiveness – my way of seeing things, the world, life – were taking shape...[7]

Shortly after his birth, Pasternak's parents had joined the Tolstoyan Movement. Novelist Leo Tolstoy was a close family friend, as Pasternak recalled, "my father illustrated his books, went to see him, revered him, and ...the whole house was imbued with his spirit."[8]

In a 1956 essay, Pasternak recalled his father's feverish work creating illustrations for Tolstoy's novel Resurrection.[9] The novel was serialized in the journal Niva by the publisher Fyodor Marx, based in St Petersburg. The sketches were drawn from observations in such places as courtrooms, prisons and on trains, in a spirit of realism. To ensure that the sketches met the journal deadline, train conductors were enlisted to personally collect the illustrations. Pasternak wrote,

My childish imagination was struck by the sight of a train conductor in his formal railway uniform, standing waiting at the door of the kitchen as if he were standing on a railway platform at the door of a compartment that was just about to leave the station. Joiner's glue was boiling on the stove. The illustrations were hurriedly wiped dry, fixed, glued on pieces of cardboard, rolled up, tied up. The parcels, once ready, were sealed with sealing wax and handed to the conductor.[9]

According to Max Hayward, "In November 1910, when Tolstoy fled from his home and died in the stationmaster's house at Astapovo, Leonid Pasternak was informed by telegram and he went there immediately, taking his son Boris with him, and made a drawing of Tolstoy on his deathbed."[10]

Regular visitors to the Pasternaks' home also included Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin, Lev Shestov, Rainer Maria Rilke. Pasternak aspired first to be a musician.[11] Inspired by Scriabin, Pasternak briefly was a student at the Moscow Conservatory. In 1910 he abruptly left for the University of Marburg in Germany, where he studied under neo-Kantian philosophers Hermann Cohen, Nicolai Hartmann and Paul Natorp.

Life and career[edit]

Olga Freidenberg[edit]

In 1910 Pasternak was reunited with his cousin Olga Freidenberg (1890–1955). They had shared the same nursery but been separated when the Freidenberg family moved to Saint Petersburg. They fell in love immediately but were never lovers. The romance, however, is made clear from their letters, Pasternak writing:

You do not know how my tormenting feeling grew and grew until it became obvious to me and to others. As you walked beside me with complete detachment, I could not express it to you. It was a rare sort of closeness, as if we two, you and I, were in love with something that was utterly indifferent to both of us, something that remained aloof from us by virtue of its extraordinary inability to adapt to the other side of life.

The cousins' initial passion developed into a lifelong close friendship. From 1910 Pasternak and Freidenberg exchanged frequent letters, and their correspondence lasted over 40 years until 1954. The cousins last met in 1936.[12][13]

Ida Wissotzkaya[edit]

Pasternak fell in love with Ida Wissotzkaya, a girl from a notable Moscow Jewish family of tea merchants, whose company Wissotzky Tea was the largest tea company in the world. Pasternak had tutored her in the final class of high school. He helped her prepare for finals. They met in Marburg during the summer of 1912 when Boris' father, Leonid Pasternak, painted her portrait.[14]

Although Professor Cohen encouraged him to remain in Germany and to pursue a Philosophy doctorate, Pasternak decided against it. He returned to Moscow around the time of the outbreak of the First World War. In the aftermath of events, Pasternak proposed marriage to Ida. However, the Wissotzky family was disturbed by Pasternak's poor prospects and persuaded Ida to refuse him. She turned him down and he told of his love and rejection in the poem "Marburg" (1917):[14]

I quivered. I flared up, and then was extinguished.

I shook. I had made a proposal—but late,

Too late. I was scared, and she had refused me.

I pity her tears, am more blessed than a saint.

Around this time, when he was back in Russia, he joined the Russian Futurist group Centrifuge (Tsentrifuga) [15] as a pianist: poetry was just a hobby for him then.[16] It was in their group journal, Lirika, where some of his earliest poems were published. His involvement with the Futurist movement as a whole reached its peak when, in 1914, he published a satirical article in Rukonog, which attacked the jealous leader of the "Mezzanine of Poetry", Vadim Shershenevich, who was criticizing Lirika and the Ego-Futurists because Shershenevich himself was barred from collaborating with Centrifuge, the reason being that he was such a talentless poet.[15] The action eventually caused a verbal battle amongst several members of the groups, fighting for recognition as the first, truest Russian Futurists; these included the Cubo-Futurists, who were by that time already notorious for their scandalous behaviour. Pasternak's first and second books of poetry were published shortly after these events.[17]

Another failed love affair in 1917 inspired the poems in his third and first major book, My Sister, Life. His early verse cleverly dissimulates his preoccupation with Immanuel Kant's philosophy. Its fabric includes striking alliterations, wild rhythmic combinations, day-to-day vocabulary, and hidden allusions to his favourite poets such as Rilke, Lermontov, Pushkin and German-language Romantic poets.

During World War I, Pasternak taught and worked at a chemical factory in Vsevolodo-Vilva near Perm, which undoubtedly provided him with material for Dr. Zhivago many years later. Unlike the rest of his family and many of his closest friends, Pasternak chose not to leave Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. According to Max Hayward,

Pasternak remained in Moscow throughout the Civil War (1918–1920), making no attempt to escape abroad or to the White-occupied south, as a number of other Russian writers did at the time. No doubt, like Yuri Zhivago, he was momentarily impressed by the "splendid surgery" of the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, but – again to judge by the evidence of the novel, and despite a personal admiration for Vladimir Lenin, whom he saw at the 9th Congress of Soviets in 1921 – he soon began to harbor profound doubts about the claims and credentials of the regime, not to mention its style of rule. The terrible shortages of food and fuel, and the depredations of the Red Terror, made life very precarious in those years, particularly for the "bourgeois" intelligentsia. In a letter written to Pasternak from abroad in the twenties, Marina Tsvetayeva reminded him of how she had run into him in the street in 1919 as he was on the way to sell some valuable books from his library in order to buy bread. He continued to write original work and to translate, but after about the middle of 1918 it became almost impossible to publish. The only way to make one's work known was to declaim it in the several "literary" cafes which then sprang up, or – anticipating samizdat – to circulate it in manuscript. It was in this way that My Sister, Life first became available to a wider audience.[18]

When it finally was published in 1922, Pasternak's My Sister, Life revolutionised Russian poetry. It made Pasternak the model for younger poets, and decisively changed the poetry of Osip Mandelshtam, Marina Tsvetayeva and others.

Following My Sister, Life, Pasternak produced some hermetic pieces of uneven quality, including his masterpiece, the lyric cycle Rupture (1921). Both Pro-Soviet writers and their White émigré equivalents applauded Pasternak's poetry as pure, unbridled inspiration.

In the late 1920s, he also participated in the much celebrated tripartite correspondence with Rilke and Tsvetayeva.[19] As the 1920s wore on, however, Pasternak increasingly felt that his colourful style was at odds with a less educated readership. He attempted to make his poetry more comprehensible by reworking his earlier pieces and starting two lengthy poems on the Russian Revolution of 1905. He also turned to prose and wrote several autobiographical stories, notably "The Childhood of Luvers" and "Safe Conduct". (The collection Zhenia's Childhood and Other Stories would be published in 1982.)[20]

In 1922 Pasternak married Evgeniya Lurye (Евгения Лурье), a student at the Art Institute. The following year their son Yevgenii was born.

Evidence of Pasternak's support of still-revolutionary members of the leadership of the Communist Party as late as 1926 is indicated by his poem "In Memory of Reissner"[21] presumably written upon the premature death from typhus of Bolshevik leader Larisa Reisner aged 30 in February of that year.

By 1927, Pasternak's close friends Vladimir Mayakovsky and Nikolai Aseyev were advocating the complete subordination of the arts to the needs of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[22] In a letter to his sister Josephine, Pasternak wrote of his intentions to "break off relations" with both of them. Although he expressed that it would be deeply painful, Pasternak explained that it could not be prevented. He explained:

They don't in any way measure up to their exalted calling. In fact, they've fallen short of it but – difficult as it is for me to understand – a modern sophist might say that these last years have actually demanded a reduction in conscience and feeling in the name of greater intelligibility. Yet now the very spirit of the times demands great, courageous purity. And these men are ruled by trivial routine. Subjectively, they're sincere and conscientious. But I find it increasingly difficult to take into account the personal aspect of their convictions. I'm not out on my own – people treat me well. But all that only holds good up to a point. It seems to me that I've reached that point.[23]

By 1932, Pasternak had strikingly reshaped his style to make it more understandable to the general public and printed the new collection of poems, aptly titled The Second Birth. Although its Caucasian pieces were as brilliant as the earlier efforts, the book alienated the core of Pasternak's refined audience abroad, which was largely composed of anti-communist émigrés.

In 1932 Pasternak fell in love with Zinaida Neuhaus, the wife of the Russian pianist Heinrich Neuhaus. They both got divorces and married two years later.

He continued to change his poetry, simplifying his style and language through the years, as expressed in his next book, Early Trains (1943).

Stalin Epigram[edit]

In April 1934 Osip Mandelstam recited his "Stalin Epigram" to Pasternak. After listening, Pasternak told Mandelstam: "I didn't hear this, you didn't recite it to me, because, you know, very strange and terrible things are happening now: they've begun to pick people up. I'm afraid the walls have ears and perhaps even these benches on the boulevard here may be able to listen and tell tales. So let's make out that I heard nothing."[24]

On the night of 14 May 1934, Mandelstam was arrested at his home based on a warrant signed by NKVD boss Genrikh Yagoda. Devastated, Pasternak went immediately to the offices of Izvestia and begged Nikolai Bukharin to intercede on Mandelstam's behalf.

Soon after his meeting with Bukharin, the telephone rang in Pasternak's Moscow apartment. A voice from the Kremlin said, "Comrade Stalin wishes to speak with you."[24] According to Ivinskaya, Pasternak was struck dumb. "He was totally unprepared for such a conversation. But then he heard his voice, the voice of Stalin, coming over the line. The Leader addressed him in a rather bluff uncouth fashion, using the familiar thou form: 'Tell me, what are they saying in your literary circles about the arrest of Mandelstam?'" Flustered, Pasternak denied that there was any discussion or that there were any literary circles left in Soviet Russia. Stalin went on to ask him for his own opinion of Mandelstam. In an "eager fumbling manner" Pasternak explained that he and Mandelstam each had a completely different philosophy about poetry. Stalin finally said, in a mocking tone of voice: "I see, you just aren't able to stick up for a comrade", and put down the receiver.[24]

Great Purge[edit]

According to Pasternak, during the 1937 show trial of General Iona Yakir and Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the Union of Soviet Writers requested all members to add their names to a statement supporting the death penalty for the defendants. Pasternak refused to sign, even after leadership of the Union visited and threatened him.[25] Soon after, Pasternak appealed directly to Stalin, describing his family's strong Tolstoyan convictions and putting his own life at Stalin's disposal; he said that he could not stand as a self-appointed judge of life and death. Pasternak was certain that he would be arrested,[25] but instead Stalin is said to have crossed Pasternak's name off an execution list, reportedly declaring, "Do not touch this cloud dweller" (or, in another version, "Leave that holy fool alone!").[26]

Pasternak's close friend Titsian Tabidze did fall victim to the Great Purge. In an autobiographical essay published in the 1950s, Pasternak described the execution of Tabidze and the suicides of Marina Tsvetaeva and Paolo Iashvili.

Ivinskaya wrote, "I believe that between Stalin and Pasternak there was an incredible, silent duel."[27]

World War II[edit]

When the Luftwaffe began bombing Moscow, Pasternak immediately began to serve as a fire warden on the roof of the writer's building on Lavrushinski Street. According to Ivinskaya, he repeatedly helped to dispose of German bombs which fell on it.[28]

In 1943, Pasternak was finally granted permission to visit the soldiers at the front. He bore it well, considering the hardships of the journey (he had a weak leg from an old injury), and he wanted to go to the most dangerous places. He read his poetry and talked extensively with the active and injured troops.[28]

Pasternak later said, "If, in a bad dream, we had seen all the horrors in store for us after the war, we should not have been sorry to see Stalin fall, together with Hitler. Then, an end to the war in favour of our allies, civilized countries with democratic traditions, would have meant a hundred times less suffering for our people than that which Stalin again inflicted on it after his victory."[29]

Olga Ivinskaya[edit]

In October 1946, the twice-married Pasternak met Olga Ivinskaya, a 34 year old single mother employed by Novy Mir. Deeply moved by her resemblance to his first love Ida Vysotskaya,[30] Pasternak gave Ivinskaya several volumes of his poetry and literary translations. Although Pasternak never left his wife Zinaida, he started an extramarital relationship with Ivinskaya that would last for the remainder of Pasternak's life. Ivinskaya later recalled, "He phoned almost every day and, instinctively fearing to meet or talk with him, yet dying of happiness, I would stammer out that I was 'busy today.' But almost every afternoon, toward the end of working hours, he came in person to the office and often walked with me through the streets, boulevards, and squares all the way home to Potapov Street. 'Shall I make you a present of this square?' he would ask."

She gave him the phone number of her neighbour Olga Volkova who resided below. In the evenings, Pasternak would phone and Volkova would signal by Olga banging on the water pipe which connected their apartments.[31]

When they first met, Pasternak was translating the verse of the Hungarian national poet, Sándor Petőfi. Pasternak gave his lover a book of Petőfi with the inscription, "Petőfi served as a code in May and June 1947, and my close translations of his lyrics are an expression, adapted to the requirements of the text, of my feelings and thoughts for you and about you. In memory of it all, B.P., 13 May 1948."

Pasternak later noted on a photograph of himself: "Petőfi is magnificent with his descriptive lyrics and picture of nature, but you are better still. I worked on him a good deal in 1947 and 1948, when I first came to know you. Thank you for your help. I was translating both of you."[32] Ivinskaya would later describe the Petőfi translations as "a first declaration of love".[33]

According to Ivinskaya, Zinaida Pasternak was infuriated by her husband's infidelity. Once, when his younger son Leonid fell seriously ill, Zinaida extracted a promise from her husband, as they stood by the boy's sickbed, that he would end his affair with Ivinskaya. Pasternak asked Luisa Popova, a mutual friend, to tell Ivinskaya about his promise. Popova told him that he must do it himself. Soon after, Ivinskaya happened to be ill at Popova's apartment, when suddenly Zinaida Pasternak arrived and confronted her.

Ivinskaya later recalled,

But I became so ill through loss of blood that she and Luisa had to get me to the hospital, and I no longer remember exactly what passed between me and this heavily built, strong-minded woman, who kept repeating how she didn't give a damn for our love and that, although she no longer loved [Boris Leonidovich] herself, she would not allow her family to be broken up. After my return from the hospital, Boris came to visit me, as though nothing had happened, and touchingly made his peace with my mother, telling her how much he loved me. By now she was pretty well used to these funny ways of his.[18]

In 1948, Pasternak advised Ivinskaya to resign her job at Novy Mir, which was becoming extremely difficult due to their relationship. In the aftermath, Pasternak began to instruct her in translating poetry. In time, they began to refer to her apartment on Potapov Street as, "Our Shop".

On the evening of 6 October 1949, Ivinskaya was arrested at her apartment by the KGB. Ivinskaya relates in her memoirs that, when the agents burst into her apartment, she was at her typewriter working on translations of the Korean poet Won Tu-Son. Her apartment was ransacked and all items connected with Pasternak were piled up in her presence. Ivinskaya was taken to the Lubyanka Prison and repeatedly interrogated, where she refused to say anything incriminating about Pasternak. At the time, she was pregnant with Pasternak's child and had a miscarriage early in her ten-year sentence in the GULAG.

Upon learning of his mistress' arrest, Pasternak telephoned Liuisa Popova and asked her to come at once to Gogol Boulevard. She found him sitting on a bench near the Palace of Soviets Metro Station. Weeping, Pasternak told her, "Everything is finished now. They've taken her away from me and I'll never see her again. It's like death, even worse."[34]

According to Ivinskaya, "After this, in conversation with people he scarcely knew, he always referred to Stalin as a 'murderer.' Talking with people in the offices of literary periodicals, he often asked: 'When will there be an end to this freedom for lackeys who happily walk over corpses to further their own interests?' He spent a good deal of time with Akhmatova—who in those years was given a very wide berth by most of the people who knew her. He worked intensively on the second part of Doctor Zhivago."[34]

In a 1958 letter to a friend in West Germany, Pasternak wrote, "She was put in jail on my account, as the person considered by the secret police to be closest to me, and they hoped that by means of a gruelling interrogation and threats they could extract enough evidence from her to put me on trial. I owe my life, and the fact that they did not touch me in those years, to her heroism and endurance."[35]

Translating Goethe[edit]

Pasternak's translation of the first part of Faust led him to be attacked in the August 1950 edition of Novy Mir. The critic accused Pasternak of distorting Goethe's "progressive" meanings to support "the reactionary theory of 'pure art'", as well as introducing aesthetic and individualist values. In a subsequent letter to the daughter of Marina Tsvetaeva, Pasternak explained that the attack was motivated by the fact that the supernatural elements of the play, which Novy Mir considered, "irrational", had been translated as Goethe had written them. Pasternak further declared that, despite the attacks on his translation, his contract for the second part had not been revoked.[36]

Khrushchev thaw[edit]

When Stalin died of a stroke on 5 March 1953, Ivinskaya was still imprisoned in the Gulag, and Pasternak was in Moscow. Across the nation, there were waves of panic, confusion, and public displays of grief. Pasternak wrote, "Men who are not free... always idealize their bondage."[37]

After her release, Pasternak's relationship with Ivinskaya picked up where it had left off. Soon after he confided in her, "For so long we were ruled over by a madman and a murderer, and now by a fool and a pig. The madman had his occasional flights of fancy, he had an intuitive feeling for certain things, despite his wild obscurantism. Now we are ruled over by mediocrities."[38] During this period, Pasternak delighted in reading a clandestine copy of George Orwell's Animal Farm in English. In conversation with Ivinskaya, Pasternak explained that the pig dictator Napoleon, in the novel, "vividly reminded" him of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.[38]

Doctor Zhivago[edit]

Although it contains passages written in the 1910s and 1920s, Doctor Zhivago was not completed until 1955. Pasternak submitted the novel to Novy Mir in 1956, which refused publication due to its rejection of socialist realism.[39] The author, like his protagonist Yuri Zhivago, showed more concern for the welfare of individual characters than for the "progress" of society. Censors also regarded some passages as anti-Soviet, especially the novel's criticisms[40] of Stalinism, Collectivisation, the Great Purge, and the Gulag.

Pasternak's fortunes were soon to change, however. In March 1956, the Italian Communist Party sent a journalist, Sergio D'Angelo, to work in the Soviet Union, and his status as a journalist as well as his membership in the Italian Communist Party allowed him to have access to various aspects of the cultural life in Moscow at the time. A Milan publisher, the communist Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, had also given him a commission to find new works of Soviet literature that would be appealing to Western audiences, and upon learning of Doctor Zhivago's existence, D'Angelo travelled immediately to Peredelkino and offered to submit Pasternak's novel to Feltrinelli's company for publication. At first Pasternak was stunned. Then he brought the manuscript from his study and told D'Angelo with a laugh, "You are hereby invited to watch me face the firing squad."[41]

According to Lazar Fleishman, Pasternak was aware that he was taking a huge risk. No Soviet author had attempted to deal with Western publishers since the 1920s, when such behavior led the Soviet State to declare war on Boris Pilnyak and Evgeny Zamyatin. Pasternak, however, believed that Feltrinelli's Communist affiliation would not only guarantee publication, but might even force the Soviet State to publish the novel in Russia.[42]

In a rare moment of agreement, both Olga Ivinskaya and Zinaida Pasternak were horrified by the submission of Doctor Zhivago to a Western publishing house. Pasternak, however, refused to change his mind and informed an emissary from Feltrinelli that he was prepared to undergo any sacrifice in order to see Doctor Zhivago published.[43]

In 1957, Feltrinelli announced that the novel would be published by his company. Despite repeated demands from visiting Soviet emissaries, Feltrinelli refused to cancel or delay publication. According to Ivinskaya, "He did not believe that we would ever publish the manuscript here and felt he had no right to withhold a masterpiece from the world – this would be an even greater crime."[44] The Soviet government forced Pasternak to cable the publisher to withdraw the manuscript, but he sent separate, secret letters advising Feltrinelli to ignore the telegrams.[45]

Helped considerably by the Soviet campaign against the novel (as well as by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency's secret purchase of hundreds of copies of the book as it came off the presses around the world – see "Nobel Prize" section below), Doctor Zhivago became an instant sensation throughout the non-Communist world upon its release in November 1957. In the State of Israel, however, Pasternak's novel was sharply criticized for its assimilationist views towards the Jewish people. When informed of this, Pasternak responded, "No matter. I am above race..."[46] According to Lazar Fleishman, Pasternak had written the disputed passages prior to Israeli independence. At the time, Pasternak had also been regularly attending Russian Orthodox Divine Liturgy. Therefore, he believed that Soviet Jews converting to Christianity was preferable to assimilating into atheism and Stalinism.[47]

The first English translation of Doctor Zhivago was hastily produced by Max Hayward and Manya Harari in order to coincide with overwhelming public demand. It was released in August 1958, and remained the only edition available for more than fifty years. Between 1958 and 1959, the English language edition spent 26 weeks at the top of The New York Times' bestseller list.

Ivinskaya's daughter Irina circulated typed copies of the novel in Samizdat. Although no Soviet critics had read the banned novel, Doctor Zhivago was pilloried in the State-owned press. Similar attacks led to a humorous Russian saying, "I haven't read Pasternak, but I condemn him".[48]

During the aftermath of the Second World War, Pasternak had composed a series of poems on Gospel themes. According to Ivinskaya, Pasternak had regarded Stalin as a "giant of the pre-Christian era." Therefore, Pasternak's decision to write Christian poetry was "a form of protest".[49]

On 9 September 1958, the Literary Gazette critic Viktor Pertsov retaliated by denouncing "the decadent religious poetry of Pasternak, which reeks of mothballs from the Symbolist suitcase of 1908–10 manufacture."[50] Furthermore, the author received much hate mail from Communists both at home and abroad. According to Ivinskaya, Pasternak continued to receive such letters for the remainder of his life.[51]

In a letter written to his sister Josephine, however, Pasternak recalled the words of his friend Ekaterina Krashennikova upon reading Doctor Zhivago. She had said, "Don't forget yourself to the point of believing that it was you who wrote this work. It was the Russian people and their sufferings who created it. Thank God for having expressed it through your pen."[52]

Nobel Prize[edit]

According to Yevgeni Borisovich Pasternak, "Rumors that Pasternak was to receive the Nobel Prize started right after the end of World War II. According to the former Nobel Committee head Lars Gyllensten, his nomination was discussed every year from 1946 to 1950, then again in 1957 (it was finally awarded in 1958). Pasternak guessed at this from the growing waves of criticism in USSR. Sometimes he had to justify his European fame: 'According to the Union of Soviet Writers, some literature circles of the West see unusual importance in my work, not matching its modesty and low productivity…'[53]

Meanwhile, Pasternak wrote to Renate Schweitzer[54] and his sister, Lydia Pasternak Slater.[55] In both letters, the author expressed hope that he would be passed over by the Nobel Committee in favour of Alberto Moravia. Pasternak wrote that he was wracked with torments and anxieties at the thought of placing his loved ones in danger.

On 23 October 1958, Boris Pasternak was announced as the winner of the Nobel Prize. The citation credited Pasternak's contribution to Russian lyric poetry and for his role in "continuing the great Russian epic tradition." On 25 October, Pasternak sent a telegram to the Swedish Academy: "Infinitely grateful, touched, proud, surprised, overwhelmed."[56] That same day, the Literary Institute in Moscow demanded that all its students sign a petition denouncing Pasternak and his novel. They were further ordered to join a "spontaneous" demonstration demanding Pasternak's exile from the Soviet Union.[57] Also on that day, the Literary Gazette published a letter which was sent to B. Pasternak in September 1956 by the editors of the Soviet literary journal Novy Mir to justify their rejection of Doctor Zhivago. In publishing this letter the Soviet authorities wished to justify the measures they had taken against the author and his work.[58] On 26 October, the Literary Gazette ran an article by David Zaslavski entitled, Reactionary Propaganda Uproar over a Literary Weed.[59]

According to Solomon Volkov:

The anti-Pasternak campaign was organized in the worst Stalin tradition: denunciations in Pravda and other newspapers; publications of angry letters from, "ordinary Soviet workers", who had not read the book; hastily convened meetings of Pasternak's friends and colleagues, at which fine poets like Vladimir Soloukin, Leonid Martynov, and Boris Slutsky were forced to censure an author they respected. Slutsky, who in his brutal prose-like poems had created an image for himself as a courageous soldier and truth-lover, was so tormented by his anti-Pasternak speech that he later went insane. On October 29, 1958, at the plenum of the Central Committee of the Young Communist League, dedicated to the Komsomol's fortieth anniversary, its head, Vladimir Semichastny, attacked Pasternak before an audience of 14,000 people, including Khrushchev and other Party leaders. Semishastny first called Pasternak, "a mangy sheep", who pleased the enemies of the Soviet Union with, "his slanderous so-called work." Then Semichastny (who became head of the KGB in 1961) added that, "this man went and spat in the face of the people." And he concluded with, "If you compare Pasternak to a pig, a pig would not do what he did," because a pig, "never shits where it eats." Khrushchev applauded demonstratively. News of that speech drove Pasternak to the brink of suicide. It has recently come to light that the real author of Semichastny's insults was Khrushchev, who had called the Komsomol leader the night before and dictated his lines about the mangy sheep and the pig, which Semichastny described as a, "typically Khrushchevian, deliberately crude, unceremoniously scolding."[60]

Furthermore, Pasternak was informed that, if he traveled to Stockholm to collect his Nobel Medal, he would be refused re-entry to the Soviet Union. As a result, on 29 October Pasternak sent a second telegram to the Nobel Committee: "In view of the meaning given the award by the society in which I live, I must renounce this undeserved distinction which has been conferred on me. Please do not take my voluntary renunciation amiss."[61] The Swedish Academy announced: "This refusal, of course, in no way alters the validity of the award. There remains only for the Academy, however, to announce with regret that the presentation of the Prize cannot take place."[62] According to Yevgenii Pasternak, "I couldn't recognize my father when I saw him that evening. Pale, lifeless face, tired painful eyes, and only speaking about the same thing: 'Now it all doesn't matter, I declined the Prize.'"[53]

Deportation plans[edit]

Despite his decision to decline the award, the Union of Soviet Writers continued to demonise Pasternak in the State-owned press. Furthermore, he was threatened at the very least with formal exile to the West. In response, Pasternak wrote directly to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev,

I am addressing you personally, the C.C. of the C.P.S.S., and the Soviet Government. From Comrade Semichastny's speech I learn that the government, 'would not put any obstacles in the way of my departure from the U.S.S.R.' For me this is impossible. I am tied to Russia by birth, by my life and work. I cannot conceive of my destiny separate from Russia, or outside it. Whatever my mistakes or failings, I could not imagine that I should find myself at the center of such a political campaign as has been worked up round my name in the West. Once I was aware of this, I informed the Swedish Academy of my voluntary renunciation of the Nobel Prize. Departure beyond the borders of my country would for me be tantamount to death and I therefore request you not to take this extreme measure with me. With my hand on my heart, I can say that I have done something for Soviet literature, and may still be of use to it.[63]

In The Oak and the Calf, Alexander Solzhenitsyn sharply criticized Pasternak, both for declining the Nobel Prize and for sending such a letter to Khrushchev. In her own memoirs, Olga Ivinskaya blames herself for pressuring her lover into making both decisions.

According to Yevgenii Pasternak, "She accused herself bitterly for persuading Pasternak to decline the Prize. After all that had happened, open shadowing, friends turning away, Pasternak's suicidal condition at the time, one can... understand her: the memory of Stalin's camps was too fresh, [and] she tried to protect him."[53]

On 31 October 1958, the Union of Soviet Writers held a trial behind closed doors. According to the meeting minutes, Pasternak was denounced as an internal émigré and a Fascist fifth columnist. Afterwards, the attendees announced that Pasternak had been expelled from the Union. They further signed a petition to the Politburo, demanding that Pasternak be stripped of his Soviet citizenship and exiled to "his Capitalist paradise."[64] According to Yevgenii Pasternak, however, author Konstantin Paustovsky refused to attend the meeting. Yevgeny Yevtushenko did attend, but walked out in disgust.[53]

According to Yevgenii Pasternak, his father would have been exiled had it not been for Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who telephoned Khrushchev and threatened to organize a Committee for Pasternak's protection.[53]

It is possible that the 1958 Nobel Prize prevented Pasternak's imprisonment due to the Soviet State's fear of international protests. Yevgenii Pasternak believes, however, that the resulting persecution fatally weakened his father's health.[45]

Meanwhile, Bill Mauldin produced a cartoon about Pasternak that won the 1959 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. The cartoon depicts Pasternak as a GULAG inmate splitting trees in the snow, saying to another inmate: "I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?"[65]

Last years[edit]

Pasternak's post-Zhivago poetry probes the universal questions of love, immortality, and reconciliation with God.[66][67] Boris Pasternak wrote his last complete book, When the Weather Clears, in 1959.

According to Ivinskaya, Pasternak continued to stick to his daily writing schedule even during the controversy over Doctor Zhivago. He also continued translating the writings of Juliusz Słowacki and Pedro Calderón de la Barca. In his work on Calderon, Pasternak received the discreet support of Nikolai Mikhailovich Liubimov, a senior figure in the Party's literary apparatus. Ivinskaya describes Liubimov as, "a shrewd and enlightened person who understood very well that all the mudslinging and commotion over the novel would be forgotten, but that there would always be a Pasternak."[68] In a letter to his sisters in Oxford, England, Pasternak claimed to have finished translating one of Calderon's plays in less than a week.[69]

During the summer of 1959, Pasternak began writing The Blind Beauty, a trilogy of stage plays set before and after Alexander II's abolition of serfdom in Russia. In an interview with Olga Carlisle from The Paris Review, Pasternak enthusiastically described the play's plot and characters. He informed Olga Carlisle that, at the end of The Blind Beauty, he wished to depict "the birth of an enlightened and affluent middle class, open to occidental influences, progressive, intelligent, artistic".[70] However, Pasternak fell ill with terminal lung cancer before he could complete the first play of the trilogy.

Death[edit]

Boris Pasternak died of lung cancer in his dacha in Peredelkino on the evening of 30 May 1960. He first summoned his sons, and in their presence said, "Who will suffer most because of my death? Who will suffer most? Only Oliusha will, and I haven't had time to do anything for her. The worst thing is that she will suffer."[71] Pasternak's last words were, "I can't hear very well. And there's a mist in front of my eyes. But it will go away, won't it? Don't forget to open the window tomorrow."[71]

Funeral demonstration[edit]

Despite only a small notice appearing in the Literary Gazette,[71] handwritten notices carrying the date and time of the funeral were posted throughout the Moscow subway system.[71] As a result, thousands of admirers braved Militia and KGB surveillance to attend Pasternak's funeral in Peredelkino.[72]

Before Pasternak's civil funeral, Ivinskaya had a conversation with Konstantin Paustovsky. According to her,

He began to say what an authentic event the funeral was—an expression of what people really felt, and so characteristic of the Russia which stoned its prophets and did its poets to death as a matter of longstanding tradition. At such a moment, he continued indignantly, one was bound to recall the funeral of Pushkin and the Tsar's courtiers – their miserable hypocrisy and false pride. "Just think how rich they are, how many Pasternaks they have—as many as there were Pushkins in the Russia of Tsar Nicholas... Not much has changed. But what can one expect? They are afraid..."[73]

Then, in the presence of a large number of foreign journalists, the body of Pasternak was removed to the cemetery. According to Ivinskaya,

The graveside service now began. It was hard for me in my state to make out what was going on. Later, I was told that Paustovski had wanted to give the funeral address, but it was in fact Professor Asmus who spoke. Wearing a light colored suit and a bright tie, he was dressed more for some gala occasion than for a funeral. "A writer has died," he began, "who, together with Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and Tolstoy, forms part of the glory of Russian literature. Even if we cannot agree with him in everything; we all none the less owe him a debt of gratitude for setting an example of unswerving honesty, for his incorruptible conscience, and for his heroic view of his duty as a writer." Needless to say, he mentioned [Boris Leonidovich]'s, "mistakes and failings," but hastened to add that, "they do not, however, prevent us from recognizing the fact that he was a great poet." "He was a very modest man," Asmus said in conclusion, "and he did not like people to talk about him too much, so with this I shall bring my address to a close."[74]

To the horror of the assembled Party officials, however, someone with "a young and deeply anguished voice"[75] began reciting Pasternak's banned poem Hamlet.

Гул затих. Я вышел на подмостки. |

The murmurs ebb; onto the stage I enter. |

According to Ivinskaya,

At this point, the persons stage-managing the proceedings decided the ceremony must be brought to an end as quickly as possible, and somebody began to carry the lid toward the coffin. For the last time, I bent down to kiss Boris on the forehead, now completely cold... But now something unusual began to happen in the cemetery. Someone was about to put the lid on the coffin, and another person in gray trousers... said in an agitated voice: "That's enough, we don't need any more speeches! Close the coffin!" But people would not be silenced so easily. Someone in a colored, open-necked shirt who looked like a worker started to speak: "Sleep peacefully, dear Boris Leonidovich! We do not know all your works, but we swear to you at this hour: the day will come when we shall know them all. We do not believe anything bad about your book. And what can we say about all you others, all you brother writers who have brought such disgrace upon yourselves that no words can describe it. Rest in peace, Boris Leonidovich!" The man in gray trousers seized hold of other people who tried to come forward and pushed them back into the crowd: "The meeting is over, there will be no more speeches!" A foreigner expressed his indigation in broken Russian: "You can only say the meeting is over when no more people wish to speak!"[75]

The final speaker at the graveside service said,

God marks the path of the elect with thorns, and Pasternak was picked out and marked by God. He believed in eternity and he will belong to it... We excommunicated Tolstoy, we disowned Dostoevsky, and now we disown Pasternak. Everything that brings us glory we try to banish to the West... But we cannot allow this. We love Pasternak and we revere him as a poet... Glory to Pasternak![77]

As the spectators cheered, the bells of Peredelkino's Church of the Transfiguration began to toll. Written prayers for the dead were then placed upon Pasternak's forehead and the coffin was closed and buried. Pasternak's gravesite would go on to become a major shrine for members of the Soviet dissident movement.[78]

Legacy[edit]

After Pasternak's death, Ivinskaya was arrested for the second time, with her daughter, Irina Emelyanova. Both were accused of being Pasternak's link with Western publishers and of dealing in hard currency for Doctor Zhivago. All of Pasternak's letters to Ivinskaya, as well as many other manuscripts and documents, were seized by the KGB. The KGB quietly released them, Irina after one year, in 1962, and Olga in 1964.[79] By this time, Ivinskaya had served four years of an eight-year sentence, in retaliation for her role in Doctor Zhivago's publication.[80] In 1978, her memoirs were smuggled abroad and published in Paris. An English translation by Max Hayward was published the same year under the title A Captive of Time: My Years with Pasternak.

Ivinskaya was rehabilitated only in 1988. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ivinskaya sued for the return of the letters and documents seized by the KGB in 1961. The Russian Supreme Court ultimately ruled against her, stating that "there was no proof of ownership" and that the "papers should remain in the state archive".[79] Ivinskaya died of cancer on 8 September 1995.[80] A reporter on NTV compared her role to that of other famous muses for Russian poets: "As Pushkin would not be complete without Anna Kern, and Yesenin would be nothing without Isadora, so Pasternak would not be Pasternak without Olga Ivinskaya, who was his inspiration for Doctor Zhivago.".[80]

Meanwhile, Boris Pasternak continued to be pilloried by the Soviet State until Mikhail Gorbachev proclaimed Perestroika during the 1980s.

In 1980, an asteroid was named 3508 Pasternak after Boris Pasternak.[81]

In 1988, after decades of circulating in Samizdat, Doctor Zhivago was serialized in the literary journal Novy Mir.[82]

In December 1989, Yevgenii Borisovich Pasternak was permitted to travel to Stockholm in order to collect his father's Nobel Medal.[83] At the ceremony, acclaimed cellist and Soviet dissident Mstislav Rostropovich performed a Bach serenade in honor of his deceased countryman.

The Pasternak family papers are stored at the Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University. They contain correspondence, drafts of Doctor Zhivago and other writings, photographs, and other material, of Boris Pasternak and other family members.

Since 2003, during the first presidency of Vladimir Putin, the novel Doctor Zhivago has entered the Russian school curriculum, where it is read in the 11th grade of secondary school.[4]

Commemoration[edit]

In October 1984 by decision of a court, Pasternak's dacha in Peredelkino was taken from the writer's relatives and transferred to state ownership. Two years later, in 1986, the House-Museum of Boris Pasternak was founded[84] (the first house-museum in the USSR).

In 1990, the year of the poet's 100th anniversary, the Pasternak Museum opened its doors in Chistopol, in the house where the poet evacuated to during the Great Patriotic War (1941–1943),[85] and in Peredelkino, where he lived for many years until his death.[86] The head of the poet's house-museum is Natalia Pasternak, his daughter-in-law (widow of the youngest son Leonid).[87]

In 2008 a museum was opened in Vsevolodo-Vilva in the house where the budding poet lived from January to June 1916.[88][89]

In 2009 on the City Day in Perm the first Russian monument to Pasternak was erected in the square near the Opera Theater (sculptor: Elena Munc).[90][91]

A memorial plaque was installed on the house where Pasternak was born.[92]

In memory of the poet's three-time stay in Tula, on 27 May 2005 a marble memorial plaque to Pasternak was installed on the Wörmann hotel's wall, as Pasternak was a Nobel laureate and dedicated several of his works to Tula.[93]

On 20 February 2008, in Kyiv, a memorial plaque[94] was put up on the house №9 on Lipinsky Street, but seven years later it was stolen by vandals.[95]

In 2012 a monument to Boris Pasternak was erected in the district center of Muchkapsky by Z. Tsereteli.

In 1990, as part of the series "Nobel Prize Winners",[96] the USSR and Sweden ("Nobel Prize Winners – Literature")[97] issued stamps depicting Boris Pasternak.

In 2015, as part of the series "125th Annive. of the Birth of Boris Pasternak, 1890–1960", Mozambique issued a miniature sheet depicting Boris Pasternak.[98] Although this issue was acknowledged by the postal administration of Mozambique, the issue was not placed on sale in Mozambique, and was only distributed to the new issue trade by Mozambique's philatelic agent.

In 2015, as part of the series "125th Birth Anniversary of Boris Pasternak", Maldives issued a miniature sheet depicting Boris Pasternak.[99] The issue was acknowledged by the Maldive postal authorities, but only distributed by the Maldive philatelic agent for collecting purposes.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of B. Pasternak's Nobel Prize, the Principality of Monaco issued a postage stamp in his memory.[100]

On 27 January 2015, in honor of the poet's 125th birthday, the Russian Post issued an envelope with the original stamp.[101]

On 1 October 2015, a monument to Pasternak was erected in Chistopol.[citation needed]

On 10 February 2020, a celebration of the 130th birthday anniversary was held at Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy in Moscow.[102]

On 10 February 2021, Google celebrated his 131st birthday with a Google Doodle. The Doodle was displayed in Russia, Sweden, some Middle Eastern countries and some Mediterranean countries.[103]

Cultural influence[edit]

- A minor planet (3508 Pasternak) discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina in 1980 is named after him.[104]

- Russian-American singer and songwriter Regina Spektor recites a verse from "Black Spring", a 1912 poem by Pasternak in her song "Apres Moi" from her album Begin to Hope.

- Russian-Dutch composer Fred Momotenko (Alfred Momotenko) wrote a companion composition to Sergej Rachmaninov's All-Night Vigil Op 37. based on the eponymous poem from the diptych Doktor Zhivago Na Strastnoy

Adaptations[edit]

The first screen adaptation of Doctor Zhivago, adapted by Robert Bolt and directed by David Lean, appeared in 1965. The film, which toured in the roadshow tradition, starred Omar Sharif, Geraldine Chaplin, and Julie Christie. Concentrating on the love triangle aspects of the novel, the film became a worldwide blockbuster, but was unavailable in Russia until perestroika.

In 2002, the novel was adapted as a television miniseries. Directed by Giacomo Campiotti, the serial starred Hans Matheson, Alexandra Maria Lara, Keira Knightley, and Sam Neill.

The Russian TV version of 2006, directed by Aleksandr Proshkin and starring Oleg Menshikov as Zhivago, is considered [citation needed] more faithful to Pasternak's novel than David Lean's 1965 film.

Work[edit]

Poetry[edit]

Thoughts on poetry[edit]

According to Olga Ivinskaya:

In Pasternak the "all-powerful god of detail" always, it seems, revolted against the idea of turning out verse for its own sake or to convey vague personal moods. If "eternal" themes were to be dealt with yet again, then only by a poet in the true sense of the word – otherwise he should not have the strength of character to touch them at all. Poetry so tightly packed (till it crunched like ice) or distilled into a solution where "grains of true prose germinated," a poetry in which realistic detail cast a genuine spell – only such poetry was acceptable to Pasternak; but not poetry for which indulgence was required, or for which allowances had to be made – that is, the kind of ephemeral poetry which is particularly common in an age of literary conformism. [Boris Leonidovich] could weep over the "purple-gray circle" which glowed above Blok's tormented muse and he never failed to be moved by the terseness of Pushkin's sprightly lines, but rhymed slogans about the production of tin cans in the so-called "poetry" of Surkov and his like, as well as the outpourings about love in the work of those young poets who only echo each other and the classics – all this left him cold at best and for the most part made him indignant.[105]

For this reason, Pasternak regularly avoided literary cafes where young poets regularly invited them to read their verse. According to Ivinskaya, "It was this sort of thing that moved him to say: 'Who started the idea that I love poetry? I can't stand poetry.'"[105]

Also according to Ivinskaya, " 'The way they could write!' he once exclaimed – by 'they' he meant the Russian classics. And immediately afterward, reading or, rather, glancing through some verse in the Literary Gazette: 'Just look how tremendously well they've learned to rhyme! But there's actually nothing there – it would be better to say it in a news bulletin. What has poetry got to do with this?' By 'they' in this case, he meant the poets writing today."[106]

Translation[edit]

Reluctant to conform to socialist realism, Pasternak turned to translation in order to provide for his family. He soon produced acclaimed translations of Sándor Petőfi, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Rainer Maria Rilke, Paul Verlaine, Taras Shevchenko, and Nikoloz Baratashvili. Osip Mandelstam, however, privately warned him, "Your collected works will consist of twelve volumes of translations, and only one of your own work."[36]

In a 1942 letter, Pasternak declared, "I am completely opposed to contemporary ideas about translation. The work of Lozinski, Radlova, Marshak, and Chukovski is alien to me, and seems artificial, soulless, and lacking in depth. I share the nineteenth-century view of translation as a literary exercise demanding insight of a higher kind than that provided by a merely philological approach."[36]

According to Ivinskaya, Pasternak believed in not being too literal in his translations, which he felt could confuse the meaning of the text. He instead advocated observing each poem from afar to plumb its true depths.[107]

Pasternak's translations of William Shakespeare (Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra, Othello, King Henry IV (Part I) and (Part II), Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear)[108] remain deeply popular with Russian audiences because of their colloquial, modernised dialogues. Pasternak's critics, however, accused him of "pasternakizing" Shakespeare. In a 1956 essay, Pasternak wrote: "Translating Shakespeare is a task which takes time and effort. Once it is undertaken, it is best to divide it into sections long enough for the work to not get stale and to complete one section each day. In thus daily progressing through the text, the translator finds himself reliving the circumstances of the author. Day by day, he reproduces his actions and he is drawn into some of his secrets, not in theory, but practically, by experience."[109]

According to Ivinskaya:

Whenever [Boris Leonidovich] was provided with literal versions of things which echoed his own thoughts or feelings, it made all the difference and he worked feverishly, turning them into masterpieces. I remember his translating Paul Verlaine in a burst of enthusiasm like this – Art poétique (Verlaine) was after all an expression of his own beliefs about poetry.[110]

While they were both collaborating on translating Rabindranath Tagore from Bengali into Russian, Pasternak advised Ivinskaya: "1) Bring out the theme of the poem, its subject matter, as clearly as possible; 2) tighten up the fluid, non-European form by rhyming internally, not at the end of the lines; 3) use loose, irregular meters, mostly ternary ones. You may allow yourself to use assonances."[107]

Later, while she was collaborating with him on a translation of Vítězslav Nezval, Pasternak told Ivinskaya:

Use the literal translation only for the meaning, but do not borrow words as they stand from it: they are absurd and not always comprehensible. Don't translate everything, only what you can manage, and by this means try to make the translation more precise than the original – an absolute necessity in the case of such a confused, slipshod piece of work."[107]

According to Ivinskaya, however, translation was not a genuine vocation for Pasternak. She later recalled:

One day someone brought him a copy of a British newspaper in which there was a double feature under the title, "Pasternak Keeps a Courageous Silence." It said that if Shakespeare had written in Russian he would have written in the same way he was translated by Pasternak... What a pity, the article continued, that Pasternak published nothing but translations, writing his own work for himself and a small circle of intimate friends. "What do they mean by saying that my silence is courageous?" [Boris Leonidovich] commented sadly after reading all this. "I am silent because I am not printed."[111]

Music[edit]

Boris Pasternak was also a composer, and had a promising musical career as a musician ahead of him, had he chosen to pursue it. He came from a musical family: his mother was a concert pianist and a student of Anton Rubinstein and Theodor Leschetizky, and Pasternak's early impressions were of hearing piano trios in the home. The family had a dacha (country house) close to one occupied by Alexander Scriabin. Sergei Rachmaninoff, Rainer Maria Rilke and Leo Tolstoy were all visitors to the family home. His father Leonid was a painter who produced one of the most important portraits of Scriabin, and Pasternak wrote many years later of witnessing with great excitement the creation of Scriabin's Symphony No. 3 (The Divine Poem), in 1903.

Pasternak began to compose at the age of 13. The high achievements of his mother discouraged him from becoming a pianist, but – inspired by Scriabin – he entered the Moscow Conservatory, but left abruptly in 1910 at the age of twenty, to study philosophy in Marburg University. Four years later he returned to Moscow, having finally decided on a career in literature, publishing his first book of poems, influenced by Aleksandr Blok and the Russian Futurists, the same year.

Pasternak's early compositions show the clear influence of Scriabin. His single-movement Piano Sonata of 1909 shows a more mature and individual voice. Nominally in B minor, it moves freely from key to key with frequent changes of key-signature and a chromatic dissonant style that defies easy analysis. Although composed during his time at the Conservatory, the Sonata was composed at Rayki, some 40 km north-east of Moscow, where Leonid Pasternak had his painting studio and taught his students.

Selected books by Pasternak[edit]

Poetry collections[edit]

- Twin in the Clouds (1914)

- Over the Barriers (1916)

- Themes and Variations (1917)

- My Sister, Life (1922)

- Second Birth (1932)

- On Early Trains (1944)

- Selected Poems (1946)

- Poems (1954)

- When the Weather Clears (1959)

- In The Interlude: Poems 1945–1960 (1962)

Books of prose[edit]

- Safe Conduct (1931)

- The Last Summer (1934)

- Childhood (1941)

- Selected Writings (1949)

- Collected Works (1945)

- Goethe's Faust (1952)

- Essay in Autobiography (1956)

- Doctor Zhivago (1957)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Pasternak". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ F.L. Ageenko; M.V. Zarva. Slovar' udarenij (in Russian). Moscow: Russkij jazyk. p. 686.

- ^ "CIA Declassifies Agency Role in Publishing Doctor Zhivago". Central Intelligence Agency. 14 April 2014. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ a b «Не читал, но осуждаю!»: 5 фактов о романе «Доктор Живаго» 18:17, 23 October 2013, Елена Меньшенина.

- ^ "Boris Leonidovich Pasternak Biography". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Christopher Barnes; Christopher J. Barnes; Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (2004). Boris Pasternak: A Literary Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-52073-7.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 137.

- ^ Pasternak (1959), p. 25.

- ^ a b Pasternak (1959), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 16.

- ^ Boris Pasternak (1967), "Sister, My Life". Translated by C. Flayderman. Introduction by Robert Payne. Washington Square Press.

- ^ Nina V. Braginskaya (2016). "Olga Freidenberg: A Creative Mind Incarcerated". In Rosie Wyles and Edith Hall (ed.). Women Classical Scholars: Unsealing the Fountain from the Renaissance to Jacqueline de Romilly (PDF). Translated by Zara M. Tarlone. Oxford University Press. pp. 286–312. ISBN 978-0-19-108965-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "BOOKS OF THE TIMES". The New York Times. 23 June 1982.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, p. 395.

- ^ a b Christopher Barnes (2004). Boris Pasternak: a Literary Biography. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 166.

- ^ Vladimir Markov (1968). Russian Futurism: a History. University of California Press. pp. 229–230.

- ^ Gregory Freidin. "Boris Pasternak". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, p. 23.

- ^ John Bayley (5 December 1985). "Big Three". The New York Review of Books. 32. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- ^ Zhenia's Childhood and Other Stories. Allison & Busby. 1982. ISBN 978-0-85031-467-0.

- ^ Boris Pasternak (1926). "In Memory of Reissner". marxists.org. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Slater, p. 78.

- ^ Slater, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Ivinskaya, pp. 61–63.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 133.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p 135.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 80.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 12, 395, footnote 3.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 12.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 27.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 28.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, p. 86.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Ivinskaya, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 144.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, p. 142.

- ^ "Doctor Zhivago": Letter to Boris Pasternak from the Editors of Novyi Mir. Daedalus, Vol. 89, No. 3, The Russian Intelligentsia (Summer 1960), pp. 648–668.

- ^ Felicity Barringer (13 February 1987). "'Doctor Zhivago' to See Print in Soviet in '88". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Fleishman, p. 275.

- ^ Fleishman, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Fleishman, p. 276.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 203.

- ^ a b Peter Finn (26 January 2007). "The Plot Thickens A New Book Promises an Intriguing Twist to the Epic Tale of 'Doctor Zhivago'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 136.

- ^ Fleishman, pp. 264–266.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 268–271.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 134.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 231.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 230.

- ^ Slater, p. 403.

- ^ a b c d e "Boris Pasternak: Nobel Prize, Son's Memoirs". English.pravda.ru. 18 December 2003. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 220.

- ^ Slater, p. 402.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 221.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 223–224.

- ^ "Doctor Zhivago": Letter to Boris Pasternak from the Editors of Novyi Mir. Daedalus, Vol. 89, No. 3, The Russian Intelligentsia (Summer, 1960), pp. 648–668.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 224.

- ^ Solomon Volkov (2008) The Magical Chorus: A History of Russian Culture from Tolstoy to Solzhenitsyn, Alfred A. Knopf, pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-1-4000-4272-2.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 232.

- ^ Horst Frenz, ed. (1969). Literature 1901–1967. Nobel Lectures. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 9780444406859. (Via "Nobel Prize in Literature 1958 – Announcement". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 May 2007.)

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 251–261.

- ^ Bill Mauldin Beyond Willie and Joe (Library of Congress).

- ^ Hostage of Eternity: Boris Pasternak Archived 27 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine (Hoover Institution).

- ^ Conference set on Doctor Zhivago writer (Stanford Report, 28 April 2004).

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 292.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 39.

- ^ Olga Carlisle (Summer–Fall 1960). "Boris Pasternak, The Art of Fiction No. 25". The Paris Review. Summer-Fall 1960 (24).

- ^ a b c d Ivinskaya, pp. 323–326.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 328.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 330–331.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, p. 331.

- ^ Lydia Pasternak Slater (1963) Pasternak: Fifty Poems, Barnes & Noble Books, p. 57.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 331–332.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 332.

- ^ a b "OBITUARY: Olga Ivinskaya". The Independent. UK. 13 September 1995. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "Olga Ivinskaya, 83, Pasternak Muse for 'Zhivago'". The New York Times. 13 September 1995. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ "IAU Minor Planet Center". minorplanetcenter.net. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Contents Archived 9 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine of Novy Mir magazines (in Russian)

- ^ "Boris Pasternak: The Nobel Prize. Son's memoirs", Pravda, 18 December 2003.

- ^ M. Feinberg (2010). Comments from the book. B. Pasternak, Z. Pasternak The Second Birth. M.: House-Museum of Boris Pasternak. p. 469.

- ^ "Boris Pasternak museum in Chistopol". museum.prometey.org. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Information about Pasternak's house museum". Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "The monument on Boris Pasternak's grave was desecrated". rosbalt.ruaccessdate=2020-01-02. 10 November 2006.

- ^ "Pasternak's house in Vsevolodo-Vilva". museum.perm.ru. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ ""Pasternak's house" official website". dompasternaka.ru. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "The first Russian monument to Pasternak was opened in Perm". lenta.ru. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ Yu. Ignatiyeva (14 December 2006). "Bronze statue of Pasternak will return to Volkhonka". inauka.ru. Archived from the original on 16 December 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Polina Yermolayeva (28 May 2008). "Memorial plaque to Pasternak". vesti.ru. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Tula Region MEMORIES DATES 2015 Archived 11 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Tula. Aquarius (2014)

- ^ Vladimir Horowitz and Boris Pasternak's memorial plaques were stolen in Kyiv, jewishkiev.com.ua (13 November 2015).

- ^ Yaroslav Markin (16 November 2015) In Kyiv unknown vandals started their hunting season. vesti-ukr.com.

- ^ "Portrait of writer B.L. Pasternak (1890–1960)". Colnect.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Lagerkvist/Pasternak". Colnect.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "125th Annive. of the Birth of Boris Pasternak, 1890–1960". Colnect.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "125th Birth Anniversary of Boris Pasternak". Colnect.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Postage stamp dedicated to Boris Pasternak". chichkin.org. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "The 125th Birth Anniversary of B.L. Pasternak". stamppost.ru. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ -Cloud, Marcus (7 February 2020). "A celebration in honor of the 130th anniversary of Pasternak will be held at ENEA". ilawjournals.com. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Boris Pasternak's 131st Birthday". Google. 10 February 2021.

- ^ Lutz D. Schmadel (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 294. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- ^ a b Ivinskaya, p. 145.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Ivinskaya, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Pasternak (1959), p. 127.

- ^ Pasternak (1959), p. 142.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 34.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 35.

Sources[edit]

- Fleishman, Lazar (1990). Boris Pasternak: The Poet and His Politics. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07905-2.

- Pasternak, Boris (1959). I Remember: Sketches for an Autobiography. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-1-299-79306-4.

- Ivinskaya, Olga (1978). A Captive of Time: My Years with Pasternak. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-00-635336-2..

- Slater, Maya, ed. (2010). Boris Pasternak: Family Correspondence 1921–1960. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-1025-9.

Further reading[edit]

- Conquest, Robert. (1962). The Pasternak Affair: Courage of Genius. A Documentary Report. New York: J.B. Lippincott Company.

- Maguire, Robert A.; Conquest, Robert (1962). "The Pasternak Affair: Courage of Genius". Russian Review. 21 (3): 292. doi:10.2307/126724. JSTOR 126724.

- Struve, Gleb; Conquest, Robert (1963). "The Pasternak Affair: Courage of Genius". The Slavic and East European Journal. 7 (2): 183. doi:10.2307/304612. JSTOR 304612.

- Paolo Mancosu, Inside the Zhivago Storm: The Editorial Adventures of Pasternak's Masterpiece, Milan: Feltrinelli, 2013

- Griffiths, Frederick T.; Rabinowitz, Stanley J.; Fleishmann, Lazarus (2011). Epic and the Russian Novel from Gogol to Pasternak (pdf). Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History. Boston: Academic Studies Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-936235-53-7. OCLC 929351556.

- Mossman, Elliott (ed.) (1982) The Correspondence of Boris Pasternak and Olga Freidenberg 1910 – 1954, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 978-0-15-122630-6

- Peter Finn and Petra Couvee, The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book, New York: Pantheon Books, 2014

- Paolo Mancosu, Zhivago's Secret Journey: From Typescript to Book, Stanford: Hoover Press, 2016

- Anna Pasternak, Lara: The Untold Love Story and the Inspiration for Doctor Zhivago, Ecco, 2017; ISBN 978-0-06-243934-5.

- Paolo Mancosu, Moscow has Ears Everywhere: New Investigations on Pasternak and Ivinskaya, Stanford: Hoover Press, 2019

External links[edit]

- Works by or about Boris Pasternak at Internet Archive

- Free scores by Boris Pasternak at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Read Pasternak's interview with The Paris Review Summer-Fall 1960 No. 24

- Boris Pasternak on Nobelprize.org

- Pasternak profile at Poets.org

- PBS biography of Pasternak Archived 5 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Register of the Pasternak Family Papers at the Hoover Institution Archives

- profile and images at the Pasternak Trust

- pp. 36–39: Pasternak as a student at Marburg University, Germany

- Boris Pasternak poetry

- The Poems by Boris Pasternak (English)

- Boris Pasternak

- 1890 births

- 1960 deaths

- 20th-century Russian male writers

- 20th-century Russian translators

- Anti–death penalty activists

- Christian poets

- Converts to Eastern Orthodoxy from Judaism

- Deaths from lung cancer in the Soviet Union

- English–Russian translators

- French–Russian translators

- Jewish classical pianists

- Jewish poets

- Jewish writers

- Jews from the Russian Empire

- Modernist writers

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Novelists from the Russian Empire

- Pasternak family

- People from Moskovsky Uyezd

- Male poets from the Russian Empire

- Russian Jews

- Russian World War I poets

- Soviet dissidents

- Soviet male writers

- Soviet Nobel laureates

- Soviet novelists

- Soviet short story writers

- Tolstoyans

- Translators from Armenian

- Translators from Czech

- Translators from French

- Translators from Georgian

- Translators from German

- Translators from Hungarian

- Translators from Polish

- Translators from Spanish

- Translators from the Russian Empire

- Translators from Ukrainian

- Translators of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Translators of William Shakespeare

- Translators to Russian

- Ukrainian–Russian translators

- World War II poets

- Writers from Moscow

- Writers from the Russian Empire

- Moscow Conservatory alumni